About Koto

Koto is Japan’s traditional string instrument

Possessing a long instrumental body which symbolizes one of the most sacred creatures in Chinese myths and legends, the koto and the dragon are in many ways inextricably linked. Moreover, since the instrument itself is made in the image of the dragon and embodies much of the sacredness of this creature, the parts of a koto are thus called “ryūtō / ryūzu” (竜頭) / dragon-head, “ryūbi” (竜尾) / dragon-tail, and “ryūzetsu” (竜舌) / dragon-tongue, etc.

History

Possessing a long and storied pedigree, the koto was first introduced to Japan during the 7th and 8th century from China. When the koto was first imported to Japan, it was used only by the Japanese court music called “gagaku” (雅楽). The koto used in gagaku is called “gakuso” (楽箏). Over time, it came to be used not only as an ensemble instrument but also as an accompaniment instrument for the singer.

Around the 16th century, the monk “Kenjun” (賢順) of Kyushu created “Tsukushiryu sokyoku” (筑紫流箏曲), the Tsukushi school of koto music.

Undeterred by his blindness, “Yatsuhashi Kengyo” (八橋検校) (who studied this Tsukushi style koto in the 17th century) would go on to create the koto methodology, which became the basis of what now comprises present-day koto music. At that time, the hemitonic pentatonic scale referred to as the “miyakobushi onkai” (都節音階) was prevalent among the common people and was already adopted in shamisen music. As one of the reforms, Yatsuhashi Kengyo created a new tuning called “hirajōshi” (平調子). Since Yatsuhashi Kengyo was originally a master of the “jiuta shamisen” (地歌三味線), he used this pentatonic scale to derive the hirajōshi scale, which remarkably is still used today as the formative tuning for the koto instrument.

During this period, a guild for blind men called “tōdō” (当道) was prevalent. Given Yatsuhashi Kengyo’s stature as one of the esteemed members of this hierarchically structured organization, the word “kengyo” (検校) hence became referred to as the highest-ranking member of the tōdō. This tōdō, in turn, received protection from the shogunate and, moreover, was granted various exclusive rights as professional music performers. Consequently, the koto was initially (a proprietary patent) performed solely by the blind artist guild, and as such barred ordinary civilians from becoming professional koto performers. As the blind musicians of tōdō started teaching koto to civilians, the instrument’s infectious beauty gradually spread among the general public.

It should be noted that there are two historically significant koto schools that developed in Japan: the “Ikuta-ryu” (生田流) / Ikuta school and the “Yamada-ryu” (山田流) / Yamada school. A member of the tōdō named “Ikuta Kengyo” (生田検校) founded the Ikuta-ryu / Ikuta school based in the Kansai region (ie. Osaka, Kyoto). Ikuta Kengyo made a historic contribution by combining the koto with juita shamisen, which was previously only deemed a solo instrument to accompany one’s singing. In order for the koto to accompany the shamisen, it was only inevitable that new techniques and tone production for the instrument would further develop during this period.

Yamada-ryu / Yamada school was started by “Yamada Kengyo” (山田検校) in Edo (current day Tokyo) during the 18th century. Yamada’s school incorporated the music of “joruri” (浄瑠璃), a type of sung narrative or storytelling accompanied by a shamisen. Influenced by the joruri music, Yamada Kengyo embarked upon composing koto music which was focused on singing.

As the “Edo Bakufu” (江戸幕府) era subsided during the 19th century, the tōdō guild found itself abolished, which, in turn, further opened the floodgates for ordinary citizens to pursue professional koto careers. With the dawn of the Meiji era, western music was slowly introduced to Japan during this time.

Amongst the handful of great modern koto performers and composers of the 20th century is “Michio Miyagi” (宮城道雄), who composed a vast instrumental repertoire for the koto. As previously stated, koto music prior to this time frequently accompanied singing. Yet Michio Miyagi, himself a prolific composer, found ways to remarkably incorporate Western music into the classic koto repertoire. As such, he was the first modern composer to create koto concertos while reforming the musical instrument by inventing the 17-string koto / bass koto, whose distinction is highlighted by the fact that it is tuned to a diatonic scale. As a result, today the koto can not only be heard as a solo instrument but can also be performed as an ensemble featuring numerous koto players. Through the 21st century and beyond, the koto continues its traditional music heritage with singing, while also functioning as a versatile instrument capable of enhancing rock, jazz, and pops genres.

Instrument

- Construction

The koto is made of Paulownia wood. There are 13 strings stretch over a wooden body of roughly six feet. The inside of the body is hollow with two sound holes on the underside. While the original koto prototype consists of 13 strings, the instrument has adapted over time to include 17-string koto / bass koto, 20-string koto, 25-string koto, and other variations.

Traditionally, koto strings were made from silk, however, more durable materials such as tetron strings are frequently used today. It is difficult for musicians to tighten or change the strings as this is a specialized skill, therefore, the expertise of koto string-tightening craftsmen are called upon when musicians require altering of their koto strings. It should be noted that there are also koto instruments with tuning pins, which more or less gives musicians an option to adjust and tighten the strings on their own.

- Tuning

There are thirteen movable bridges called “ji” (柱)/ bridge, placed along the body of the instrument for each string. The koto player can adjust the string pitches by moving these bridges. The tuning of the koto instrument is determined by several factors such as the scale depicted in a particular song, the nature of instrument accompaniment at hand, and the measure and pitch of the singer’s vocal articulation. The grace and precision of the instrument are such that, often times, there are scale changes within the same piece requiring the koto musician to move the bridges throughout the performance.

The traditional koto uses a pentatonic modal scale system. Some of the popular minor pentatonic scales include kumoijoshi, nakazorajoshi, and hirajoshi. Once the tuning of the first string (the tonic note) is determined, one can apply the same intervals by setting the bridges in specific relationships to each other. These modal scales can be performed in all keys.

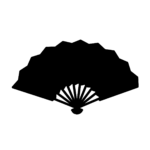

- Technique

The koto is played using three finger picks called “tsume” (爪), which are made out of plastic or ivory, while placed on the thumb, index finger and middle finger of the right hand. The three tsume picks are used to strike the strings in various technical styles. Pizzicato is also used with fingers that do not have the fitted picks to produce sound.

From a functional standpoint, the koto pitch is raised by pressing down on the string on the left side of the “ji” (柱) / bridge, with the left hand. One can lower the pitch by using their left hand, pulling the string toward the bridge and releasing it to its original pitch. Moving the bridge in itself will allow the koto performer to adjust the pitch higher or lower throughout a piece, yet another distinct feature of the remarkable instrument.

School

- Ikuta-ryu(生田流)/ Ikuta school

- Yamada-ryu(山田流)/ Yamada school

There are two, major koto schools, the “Ikuta-ryu” (生田流) / Ikuta school and the “Yamada-ryu” (山田流) / Yamada school. The schools are distinguished by the shape of their finger picks, “tsume” (爪). Ikuta-ryu uses square tsume to strike the strings using the corners of the tsume, while the Yamada-ryu uses rounded pointed tsume.

Resources

Discover additional information about the Koto below